As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. If you purchase something through an affiliate link on this page, I earn a commission at no extra cost to you.

Dear reader,

I like to think that I have overcome my habit of procrastination in the last couple years, but I must confess: there is a pea-sized part of me that is still holding onto the decaying habit. I have good reason, though! I’m not actually procrastinating; I’m just being prepared!

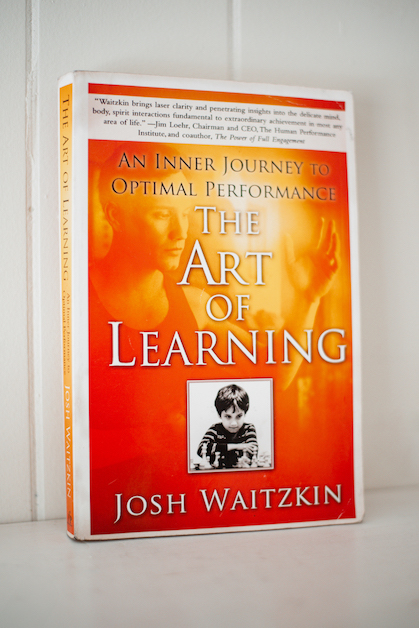

In this instance, I have decided to prepare my mind for learning by learning about learning. Make sense? In simpler terms, I Googled “books about learning”, found “The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance“, ordered it, read it, and am now rationalizing why I spent all that time learning about learning instead of actually doing it.

Well, we’re here now so I might as well tell you about it because I got some truly useful information out of the book. And I’m not even rationalizing anymore. I promise.

First, I should introduce Josh Waitzkin, the author, who is a chess prodigy and martial arts world champion. So he is, at the very least, smarter than me, who is neither a prodigy nor a world champion of any kind. Therefore, there must be something we can learn from him. Here are some lessons that were of interest to me, a beginning learner:

1. Find the right teacher.

The accomplished Mr. Waitzkin’s advice for finding a good teacher is to look for someone who takes the approach of guiding the student rather than being the omniscient authority on the subject and forcing facts and logic into the student’s willing (or secretly unwilling) ears. This method of steering the student towards mastery is done by asking questions about the student’s thought process, whether it was correct or not, and discussing rather than lecturing if there is a disagreement or glitch in the student’s understanding. In particularly feisty disagreements, the guide may be required to prove that the student is mistaken rather than just telling him to shut up and accept that he is. (Example in Chapter 1)

This is a valuable approach because a guided student is better able to understand the reasoning behind the things he is learning and is therefore better able to apply them. Personally, I sort of like being told what to do so I could fare well with a more structured teacher, but I do see the value here in assisting with a more active learning process.

The most important quality in a teacher, regardless of the approach, is that he must not dampen the student’s natural voice or enthusiasm for the topic. This can happen when there is too much of a focus on the technical aspects of whatever you’re doing, or when the creative boundaries imposed on the student are too restrictive in order to create a specific type of end result. The discouraged student may eventually give up trying. There is no point in teaching someone who no longer cares because time and energy will be expended fruitlessly. Learning requires attention. Attention requires interest. If you extinguish the interest, there will be no learning.

2. Learning Theorist > Entity Theorist

This concept is my favorite! It has completely changed my mindset about learning.

In the book, the father of another young chess competitor was so focused on winning that he made his son study chess for 12 hours a day, and it negatively affected their relationship if he lost a game. After a loss, the boy would cry for hours. The father’s approach created the Entity Theorist mindset within his son, which affected the boy’s resilience. I wouldn’t be shocked if that approach eventually made the boy hate the game itself.

Entity Theorists view the learning and competing process as a win/loss game. If they win, they’re good, and if they lose, they’re a failure. Their identity in a particular skill is based on the outcome only, and this promotes a brittle, perfectionist mindset where mistakes or losses are a bad thing. Many with this mindset can become discouraged or fail to try in the first place because they don’t want to see themselves as a loser.

Learning Theorists focus on the process and effort rather than the results. They take results into account so they know where to focus in their next practice sessions, but a win or loss does not define their identity because the Learning Theorist will always be working to improve the skill incrementally. This mindset is especially important when challenges arise. Failure is seen as part of the long-term journey, so it doesn’t discourage the learner from continuing.

This concept was mind-blowing to me because I have been an Entity Theorist all my life! When I was taking piano lessons as a kid, I would often cry before a lesson because I didn’t feel like I was good enough at the song I was practicing to play in front of my teacher. This seems ridiculous to me now because the whole point of going to the lesson was to work on ways I could improve. I wasn’t going to be Mozart after one week of playing a new song, but I felt like a failure if I wasn’t.

This theory also explains why I never tried anything new! The thought of making mistakes and embarrassing myself was overwhelming to me, so I must have been tying failure to my identity. It’s so helpful to have this articulated because now I know that my issue was my focus on the outcome instead of the process, which is insane when you consider that nobody is perfect the first time they do something. But at the time I didn’t realize this, and I began to embrace the safe mediocrity of doing nothing.

3. Fundamentals first.

Beginning with the fundamentals is vital to mastering a skill. Because of the reduced complexity, starting with the basics allows you to fully understand the concept you are trying to grasp until it becomes unconscious knowledge. From there, you can incrementally build on that foundation, and because you have started at the bottom and know the concept intuitively, you will make less mistakes and more efficiently implement the knowledge.

Mr. Waitzkin uses the example of learning chess to illustrate this idea. When he took lessons, his coach started him out using only a king and a pawn against a king. This forced him to become familiar with the limits of those particular pieces without cluttering up his mind with larger strategies that included all the pieces of the game.

He also used this knowledge on his way to becoming a Push Hands National Champion after studying Tai Chi for only two years. His skill set wasn’t as broad as the other competitors’, but the skills he did have were refined until they were potent. He mastered the fundamentals and they were effective.

When trying to learn something new, it’s easier for me to stay motivated if there’s a logical progression to it and I’m not overwhelmed with every facet of the subject at once. Similarly, in practice I do better if I am given a single correction to focus on with time to try it out. If the teacher overwhelms me with constant corrections, I try to focus on fixing too many things and struggle to implement any improvement at all. Maybe I just don’t have a high cognitive capacity, but I like things to make sense where I’m at so I can have a solid foundation to build upon.

4. Breaks are not just important, they’re necessary.

It can be tough to pull yourself away from the perceived advantages of constant training and competing, but breaks are a necessary part of the process. Mr. Waitzkin would sail to Bimini with his family every summer for weeks to fish, swim, and play in the sun, and each time he returned with renewed energy and ideas.

In the context of a game or competition, allow yourself a true mental rest from the action during a break. Don’t focus on the ongoing play or the results of the last game because you’re not allowing yourself to recover in the moment. After a break, you will reenter the game with a fresh perspective.

I’ve been taking voice lessons lately, and I’ve found this to be helpful for singing specific songs. Consistent practice is necessary to improve, but if I get frustrated or am just not getting something, I will occasionally need to take a break from a song for a week or so. This acts as a reset and I can approach the music with fresh eyes (or vocal cords). Breaks from singing itself are helpful too. If I go on a trip, I don’t practice much, and I return home with renewed motivation.

5. Weaknesses are an opportunity.

“Dirty players were my best teachers.”

– Josh Waitzkin, “The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance“

When Mr. Waitzkin came up against a dirty Push Hands opponent, they exposed his weaknesses. Headbutts and hits to certain areas of the body were against the rules, so he hadn’t trained to defend against them and therefore was weaker in that part of his skill set. He realized that to win against this type of player, he had to rely on himself and his skills rather than a referee who might not notice. So that’s what he trained for. The result was that when he came up against a dirty player again, he was able to keep his cool and defeat them.

This is a valuable lesson because when cheating occurs, the default attitude for a human to take is victimhood. Instead, he was able to see his gap in training for the opportunity it was and realize that his opponents were doing him a favor by showing him where he was weak. Had they not revealed this, he wouldn’t be as well-rounded in his defense and as practiced at staying calm in a chaotic situation. Once he developed the mindset that his weaknesses were an opportunity, he was able to take the next step and learn how to make them a strength rather than marinating in righteous indignation and allowing it to get to his head. Imagine the shock his rogue competitor felt when Josh successfully blocked illegal tactics without a second thought!

This concept goes hand in hand with the Learning Theorist mindset, which views errors as a necessary step on the road to mastery. Errors and weaknesses are the first things we should focus on, and if we take the approach of improving them when they are revealed to us, we are more likely to win.

This book contains other concepts that I haven’t discussed, such as Making Smaller Circles, getting in The Zone, and how to tap into your Intuition. Mr. Waitzkin illustrates complicated ideas in a logical way that anybody can understand and apply in their own lives.

You know what? I don’t have to rationalize. I can’t even call it procrastinating. This book has transformed my mindset so much that I can honestly say I spent my time productively, and yes, learned something.

-Madelyn